ChatGPT isn’t a decompiler… yet

Previous article: What I’m up to

Abstract / Results

It feels a bit pretentious to open a blog post with an abstract. However, I wanted to communicate up front concisely what I tried to do, and what the open areas of exploration are. Those who are interested can dig more.

I wanted to make ChatGPT into a magic decompiler for PowerPC assembly to supercharge the Super Smash Bros. Melee (“Melee”) decompilation project. I observed over a year ago that ChatGPT was surprisingly good at understanding PowerPC assembly language and generating C code that was logically equivalent. I also saw other papers that were attempting to use LLMs as decompilers.

Problem statement: given the PowerPC ASM a1 of a function f1, use AI to come up with C code that compiles to a2 where a2 == a1 (note: the C code doesn’t have to be the same as the original. There are many C programs that map to the same assembly). This is called match-based decompilation, as merely being logically equivalent is not sufficient. Also, in the case where a2 isn’t a match, iteratively improve on the result.

gpt-4o was able to often generate code that was logically similar. It was also able to iteratively correct compiler errors (even for an older dialect of C). However, it was unable to improve on its results even when given the assembly diffs in a digestible format. It showed understanding of the assembly diffs, but wasn’t able to actualize that into logical changes to the C code that brought it closer to its target. I also briefly investigated fine tuning and didn’t get results.

There are a couple of explorations left to be tried, but before I get into that, some notes about the problem space:

- This isn’t a classic RLHF problem. You don’t need human feedback at all. Especially with the automated tooling I set up, you can actually automatically “score” how close the ASM is to the target ASM. So maybe a more classic RL approach would be interesting

- Coming up with C code that compiles to the same ASM isn’t actually all that’s needed for the decompilation project. This tool wouldn’t be powerful enough to wire in struct definitions from other parts of the codebase, or even handle imports. On the other hand, LLMs with retrieval could actually be pretty good at this, and tools here would be much appreciated to the scene

What we’re trying to do

So we’re trying to write a magic-decompiler for Melee. You might ask, why do game decompilation? And why Melee? Valid questions!

Why Melee?

Simple. The game is dear to my heart even if I don’t play it that much anymore, and it’s still competitively alive today despite coming out in 2001. Also, people have already written extensive modifications for the game, and this would help both:

- power future modifications

- make it more accessible for new developers to join the fray

Game Decompilation?

There have been a bunch of successful game decompilation projects in the last couple of years, which were then followed by some really cool modifications to the games. One of my favorite ones is adding raytracing to Super Mario 64 which adds beautiful accurate shadows, reflections, and global illumination. While I dream about adding raytracing to Melee, that probably wouldn’t be a great idea since input latency is almost always the top priority when playing the game, but mods like extensive UI modifications or model swaps are definitely fair game.

Now, it’s going to get more technical. First, some background info!

Background info

Match-based decompilation

Game decompilation isn’t the same as normal decompilation that security engineers do with Ghidra. What we’re trying to do is called match-based decompilation.

Assuming a game is written in the C programming language and we have the game binary (in whatever architecture the console is in. For the Gamecube, it’s PowerPC), we want to attempt to reconstruct C code that is similar to what the game developers wrote themselves.

Note that I said similar and not identical. Compilation is inherently a lossy process, especially as you turn on optimization flags. Comments are almost always stripped out (so your // help me isn’t going to make it to prod 😋). However, there are some ways to slice similar.

Here are two C programs, \(C_1, C_2\), that are logically similar:

// Program 1

int main() {

int i = 1;

int sum = 0;

while (i <= 5) {

sum = sum + i;

i = i + 1;

}

return sum;

}

// Program 2

int sum(int n) {

if (n > 0)

return n + sum(n - 1);

return 0;

}

int main() {

return sum(5);

}

These produce drastically different assemblies, \(A_1, A_2\), when we use the compiler & flags for Melee.

# Program 1

00000000 <main>:

li r3,15

blr

# Program 2

00000000 <sum>:

# impl of int sum(), 33 lines

00000088 <main>:

mflr r0

li r3,2

stw r0,4(r1)

stwu r1,-8(r1)

bl 98 <main+0x10>

addi r3,r3,12

lwz r0,12(r1)

addi r1,r1,8

mtlr r0

blr

The compiler completely inlines the logic for \(C_1\), in that it doesn’t even compute the sum - it just directly loads the result, 15, into r3, the return register. You can probably see now how compiling can be lossy - we’ve completely lost the logic inside of main(). However, for \(C_2\), it actually generates code for the generic method int sum and also does all of the heavy-lifting to call the function.

While both C programs would be a valid decompilation in some spaces, \(C_1\) would fail to be a match decompilation if the assembly we were trying to match was \(A_2\). Specifically, C code that would yield a match is a subset of all C code that is logically equivalent to the target ASM. We have to go as far as register allocations being identical.

Here’s a more insipid example of programs that are really really similar. Here is a C program that calculates the fibonacci sequence iteratively:

int fibonacci(int n) {

int temp;

int i;

int a = 0;

int b = 1;

if (n <= 0) {

return 0;

} else if (n == 1) {

return 1;

}

for (i = 2; i <= n; ++i) {

temp = a + b;

a = b;

b = temp;

}

return b;

}

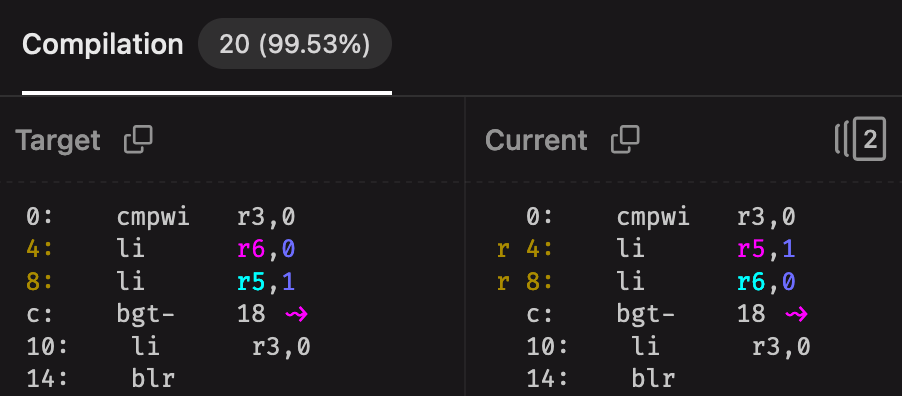

I’ve compiled this program to assembly, and then loaded it into decomp.me. Now, if we swap the declarations for a and b:

// Old

int a = 0;

int b = 1;

// New (logically equivalent)

int b = 1;

int a = 0;

we get the following ASM diff (while the registers are the same, the instructions are in a different order):

This is pretty rough; that means that variable declaration order matters even if it doesn’t affect execution. Also, while these are small errors, there are really strange ways to massage the C code in order to get the compiler to spit out some ASM; you’ll notice this especially when it’s code that triggers a compiler bug.

Now you might reasonably ask, why do we want the exact same assembly? Some reasons that are non-exhaustive:

- We want to be able to build the exact ROM of the game. This is the easiest way to verify that the game was completely decompiled, as verifying logical equivalence is non-trivial

- Some existing understanding / mods of the game being decompiled rely on the program being laid out the exact same way. Modifying this extensively will make those (albeit brittle) changes not work anymore

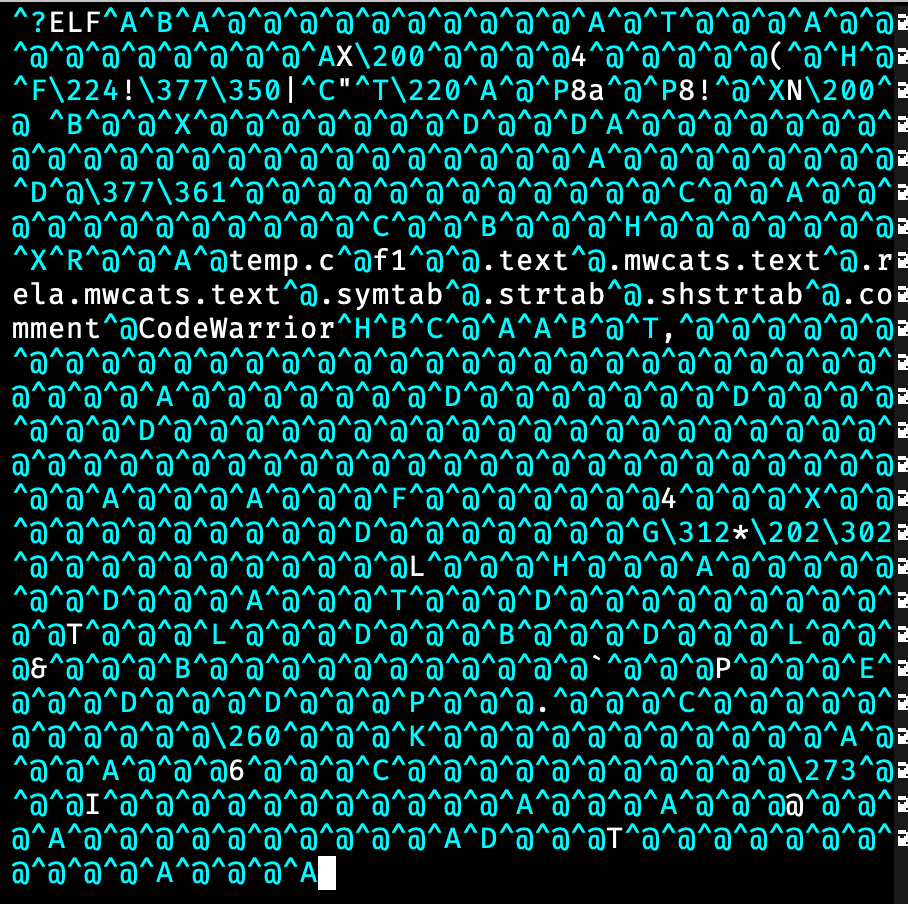

File types

- OBJ: This is the output of a compiler. It contains binary machine code that a computer can execute. This is not the readable ASM that we’re dealing with, but the binary encoding of it. Looks like gibberish when opened, with occasional strings like

"Hello"

- You can see that this file says that it’s an ELF in the “header”, which is the object file type for PowerPC.

- ASM: This is a human-readable representation of the machine code. It’s a programming language to some extent, but much lower level than C. For PowerPC, you’ll see instructions like

li r1 3.

.fn f1, global

stwu r1, -0x18(r1)

add r0, r3, r4

stw r0, 0x10(r1)

addi r3, r1, 0x10

addi r1, r1, 0x18

blr

.endfn f1

- C: This is C code, which is the closest to human-readable, and what we’re looking for

int* f1(int x, int y) {

int z = x + y;

return &z;

}

Tools

- Compiler: this converts C code to an OBJ. This is often a lossy process and the original C code cannot be recovered once you just have the OBJ file, especially as you turn on optimization flags.

- Decompiler: this would convert either OBJ or ASM -> C. For this particular project, a perfect decompiler doesn’t exist but we’re looking for something close.

- Disassembler: OBJ -> ASM. This takes a compiled object file and spits out a human-readable representation of the ASM. Sometimes, it’ll even add nice quality-of-life fixes such as changing register arguments from numbers to names like

r1orsp. - Assembler: ASM -> OBJ. This converts from an ASM to an OBJ. I needed this specifically because the ASM differ I used,

asm-differactually best worked when comparing two object files (but the whole process takes in an ASM file as input).

Specific tools to this project:

decomp.me: This is a batteries-included collaborative website where you can interactively & collaboratively decompile video games. It’s pretty crazy this exists. You barely have to understand how decompiling works to use this tool effectively; hell, I don’t think you even really need to know how to code. A lot of my project was understanding howdecomp.meworks internally.m2c(GitHub): This is the default decompiler used fordecomp.me. It’s a great starting point for when you just have ASM, don’t get me wrong, but it:- doesn’t produce code that compiles

- doesn’t really take matching into account

mwcc: this is the MetroWerks C compiler. I’m specifically using a version that’s identical (or close to) the one that the Melee team used, with the same flags as well.dtk disasm(GitHub): The disassembler I used. This tool is used by the Melee decomp project, and the assembly in the GitHub follows the output format.powerpc-eabi-as: The assembler I used.asm-differ(GitHub): The ASM differ & scorer thatdecomp.meuses. Was pretty nontrivial to get working the same way. Bothdecomp.meand my project had to do some workarounds to call it conveniently.

I’ll be referring to these formats / tools, so feel free to return to this section. I’ll also explain how to get some of these later.

What did I do?

When I was in the prototyping phase, I was just giving ChatGPT a copy-and-pasted prompt and an assembly file and plugging in the C it gave me to decomp.me. While the code was impressive and usually a close logical match, the code often didn’t compile. mwcc uses a pretty old version of C which didn’t have a lot of the features we rely on today (e.g. you have to declare all of your variables at the beginning of a function!!), and I bet that didn’t make up a lot of ChatGPT’s training set.

I then had a flashback to having crazy TypeScript errors and ChatGPT figuring out all of them at my last job. When I gave ChatGPT all of the compiler errors I had for a given C program, it was really good at fixing the problems without changing the code too much! It would usually take one or two tries to get it to compile, but when actually checking the match score, it wasn’t close to a match.

I realized that the iterative process that I did to get the code to compile could be something to automate. And not just that, I could apply this loop-improvement cycle for ASM matching. But I was pretty far from this: I was currently just holding a bundle of ASM & C files, and copying and pasting them into decomp.me. Getting the ASM from a given C program was hard for me at that time: I even wrote a script to parse the compilation results from decomp.me’s backend 😭 since I couldn’t figure out how to go from C -> OBJ -> ASM. In order to automate this whole process, I’d have to figure out how to run all of these things locally. Specifically:

- Compiling C code with

mwcc - Comparing ASM files & scoring them

- Writing a state machine that loops and either fixes compiler errors or attempts to improve the ASM match

At this point of time, I hadn’t verified if ChatGPT was capable of improving the ASM score. It was too difficult to hold onto all these C files and get them to compile while juggling around a bunch of prompts.

Compiling locally

The objective here is to be able to take a small C function, f1, and get the resulting ASM, ideally in the same format as the Melee codebase.

First, we have to start by getting the binaries! It took me a while to figure this out, but the Melee codebase has a helper tool to download a lot of the common binaries. You can just run:

ninja build/binutils

This will download a bunch of tools including the assembler we’ll be using. You also might just want to run ninja to download the rest of the tools, as we’ll also need to download

dtk- the compiler. This ends up being in

build/compilers

Once I got these binaries, I realized that some of them (namely, the compiler) are Windows programs. As I am developing on a Mac, it took some tinkering to get the compiler to work using wine. My invocation ended up looking something like this (I got the args from decomp.me):

wine bin/mwcceppc.exe -Cpp_exceptions off -proc gekko -fp hard -fp_contract on -O4,p -enum int -nodefaults -inline auto -c -o temp.o FILENAME

Once I had my .o files (OBJ), to get the ASM, you have to run it through a disassembler. I ended up calling that like this:

../melee/build/tools/dtk elf disasm outputs/temp.o temp.s

So the whole compilation flow looks something like this:

- ChatGPT generates a toy C program

- We run it through the compiler,

mwcc, to get an OBJ file - We then run the OBJ file through a disassembler,

dtk disasm, to get an assembly file,.s

Comparing ASM files and scoring them

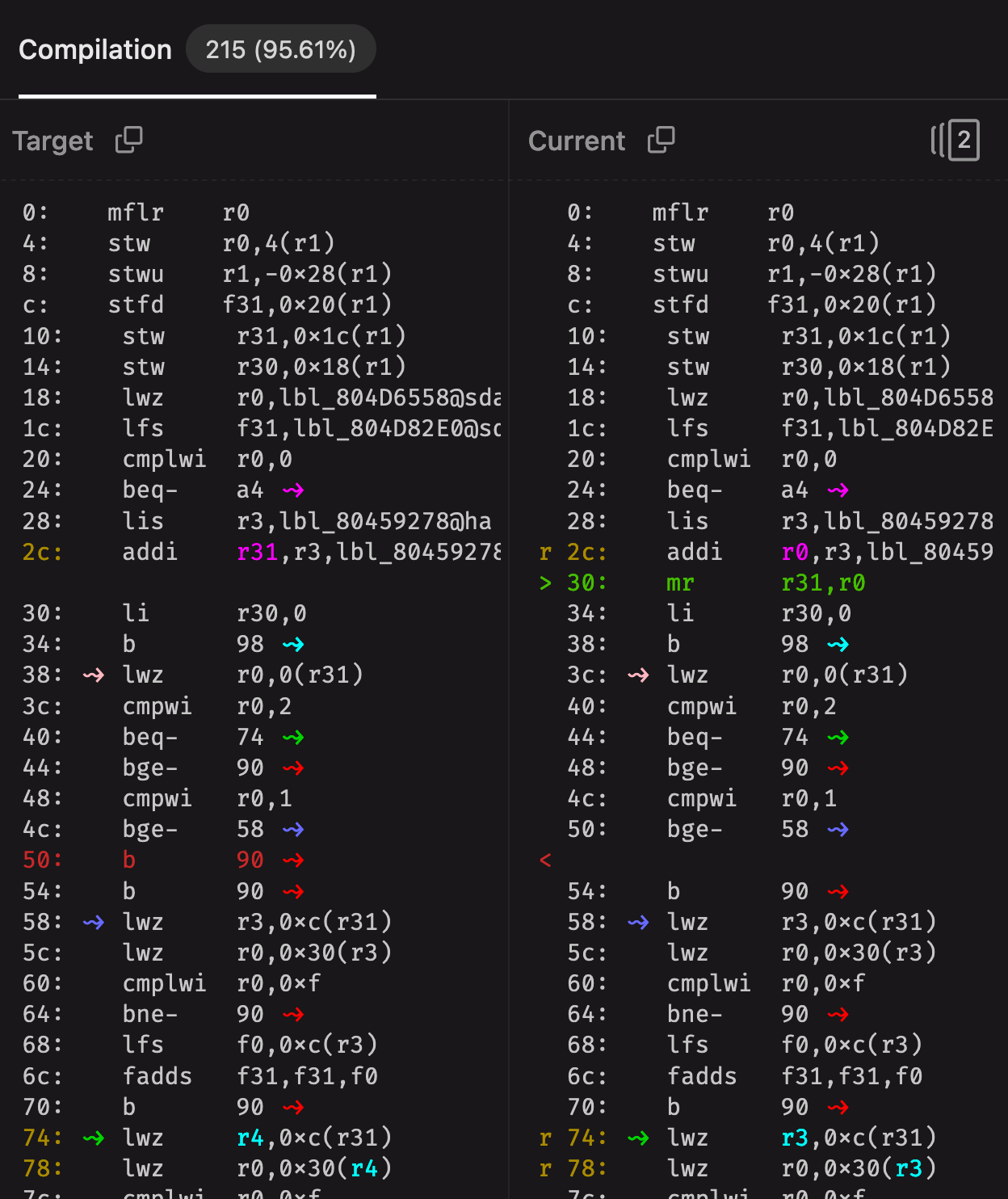

Now that we got ASM output, we want to be able to compare two ASM files. You could do something as simple as diff the two .s files. However, I noticed that decomp.me had a much more sophisticated differ, that also included scoring. I’ve shown screenshots earlier, but here’s a more complicated example:

b 90s. b is just an unconditional jump, which means that line 54 should be unreachable.

There are a lot of nice features here:

- scores. both % match as well as a number that decreases -> 0 as you get closer.

- same as

diff: lines missing or additional lines - register errors, marked with

r - not shown, but immediate errors are marked with

i

I had already tried giving ChatGPT simple diff outputs to see if it could improve the matches, and didn’t succeed, so I hoped that giving it a richer picture of the diff would improve its output.

I ended up going on a deep dive to see how decomp.me accomplished their rich ASM diff view. After some trudging through the codebase, I found where the magic happens: this file wraps a library called asm-differ (GitHub).

At first, I was excited to find out that it was a library already by itself. However, the library isn’t super easy to call for a one-off situation: it’s meant to be used with a C project. I did go through the pains of configuring it properly to make sure it’s output was what I was looking for first. Then, I ended up doing something similar to what decomp.me did - write a wrapper program that calls into internal methods of asm-differ and manufactures a project config in-memory. Here’s where I did that, and here’s where decomp.me did it. My implementation is a little janky as it definitely expects some files to be in the right places, but more on that later. The ASM diff ends up being almost exactly like the website’s, which is a huge win! 🎊

The state machine

I didn’t realize that this was a state machine at first. I went into this portion of the project like “I need to call ChatGPT in a loop, and I need to glue all of these tools together.” I was just copying and pasting long bash commands and pasting inputs and outputs into ChatGPT, and so testing many examples at scale was just not feasible.

There are two processes at play here:

- Fix errors: Given a C program that doesn’t compile, fix it while keeping the logic the same

- Improve ASM score: Given a C program that does compile but doesn’t match, try to improve the matching score.

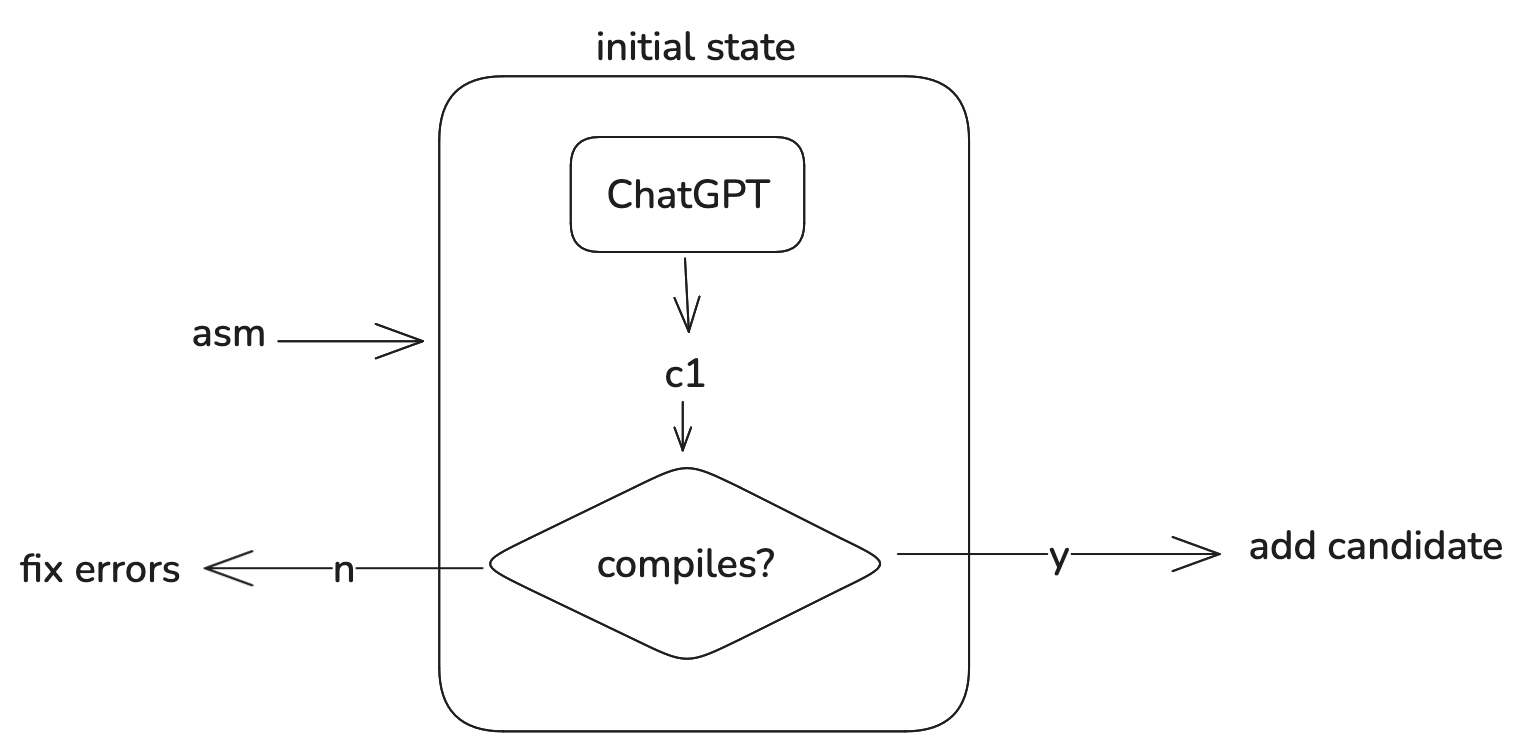

When asking ChatGPT for C code, the initial state looked like this:

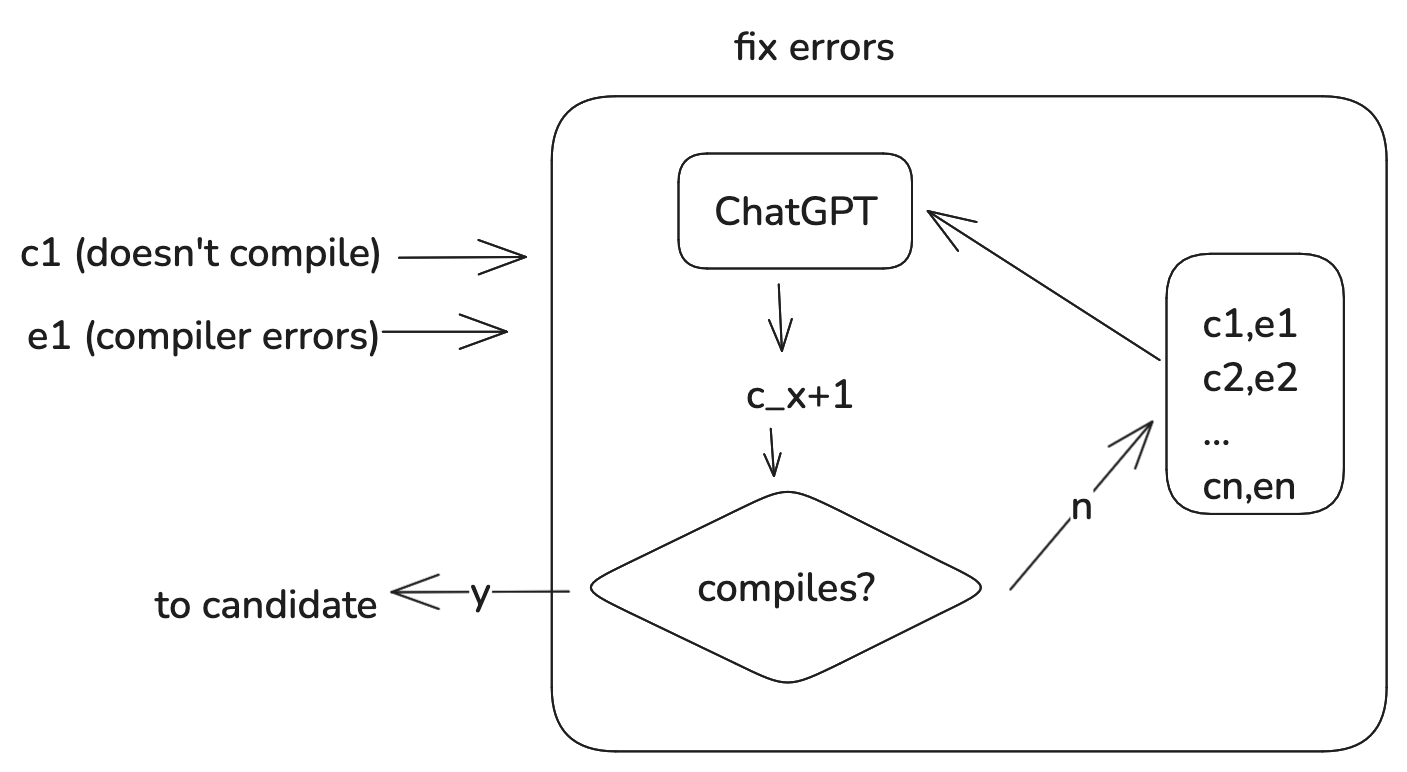

Fixing errors was pretty simple. We just compile the program, get the errors, and then ask ChatGPT to attempt to fix the errors. I initially tried to get ChatGPT to fix the errors by just pasting in the last compile run’s errors. This generally took around 5 passes to get code that compiled. A simple improvement was to send all of ChatGPT’s attempts in a chain from the last success, which then got it down to 1-2 passes. Once we get C code that compiles, we transition to (2):

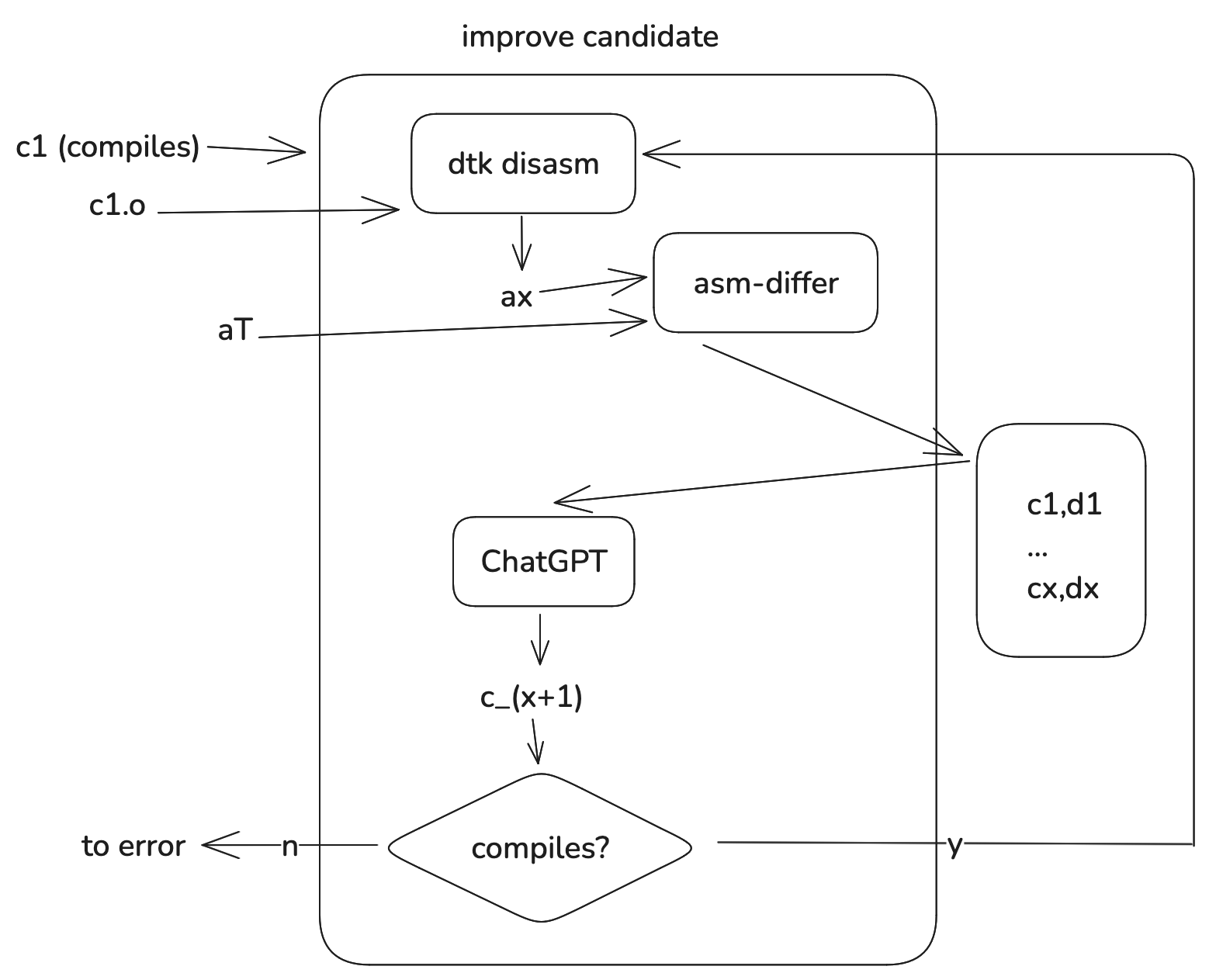

The candidate phase is a bit more interesting and actually tests the hypothesis. From a high level, we want to compare the assemblies of the C code we have and the assembly target, get a diff that is easy-to-interpret, and ask ChatGPT to attempt to improve the C code to be a closer match.

We start with a candidate, \(C_1\):

- We first need to get the ASM after compiling \(C_1\). We compile the program to get an OBJ file,

c1.o, and then we run it throughdtk disasmto get ASM \(A_1\). - Then we have to diff \(A_1\) and \(A_T\). We use

asm-differto get both a score & a line-by-line diff. Let’s call this \(D_1\). - Then, given \(C_1\), the score, and \(D_1\) (which contains both \(A_1\) and \(A_T\)), we ask ChatGPT to generate a new candidate that is a closer match.

We get \(C_2\). Now, if you’ve been following along, you can probably tell that this is going to be a loop of some kind:

Ultimately, the functionality of this program was to improve the ASM score, so I disregarded blowing up the context window for this phase since I hoped having more information would improve the loop’s result. Also, the error fixing loop actually terminated pretty quickly, so keeping track of all the \((c_x, e_x)\) pairs was unnecessary.

Testing

Now that the improvement loop was finished, it was time to run it! But before that, we need some input datasets.

Training set

The nice thing about creating a list of inputs and expected outputs is that it doubles as a training set. After doing so many manual tests, I already had an inclination that results wouldn’t be good without fine tuning.

I came up with a small training set for mwcc here. The repo is separated into 10 /general examples and 3 /melee examples. You might ask: why make so many general examples if you’re trying to decompile Melee?

The reason why is that even though we have C / ASM pairs in the Melee decompilation codebase, the code is really idiomatic aka it requires a really large set of headers / context to compile a given function. This poses the following issues:

- If we were to paste in all the context required to compile the function, it will easily exceed

4o’s token length (I did verify this myself) - Conjecture: Any fine tuning might not generalize to different functions that have unknown structs, so making it more generic would give the model a higher likelihood of generalizing

General examples were probably good enough. We wanted ChatGPT to learn the compiler’s behavior with a set of flags. Coming up with general examples was so easy:

- Ask ChatGPT to generate a toy C program with no includes, probably on a problem I’m familiar with (e.g. reversing a linked list)

- Get the code to compile. You can even ask ChatGPT to fix the errors

- Disassemble it to get the resulting ASM

- Save it as a C ASM pair

Coming up with Melee examples was harder. I essentially had to find really small functions, or attempt to rip out all the context from an already-solved portion of the Melee codebase. That means not using any structs, attempting to be closer to the ASM than even the solution, etc. It wasn’t a pleasant process and I couldn’t figure out how to automate it.

Actually testing

I ran most of the general code examples through the whole loop. The results weren’t great. ChatGPT:

- ✅ was able to fix compiler errors

- ✅ seemed to understand the ASM diffs and was able to identify issues

- ✅ was able to generate C code that logically was pretty similar or identical to the ASM

- ❌ was not able to substantially improve the match score.

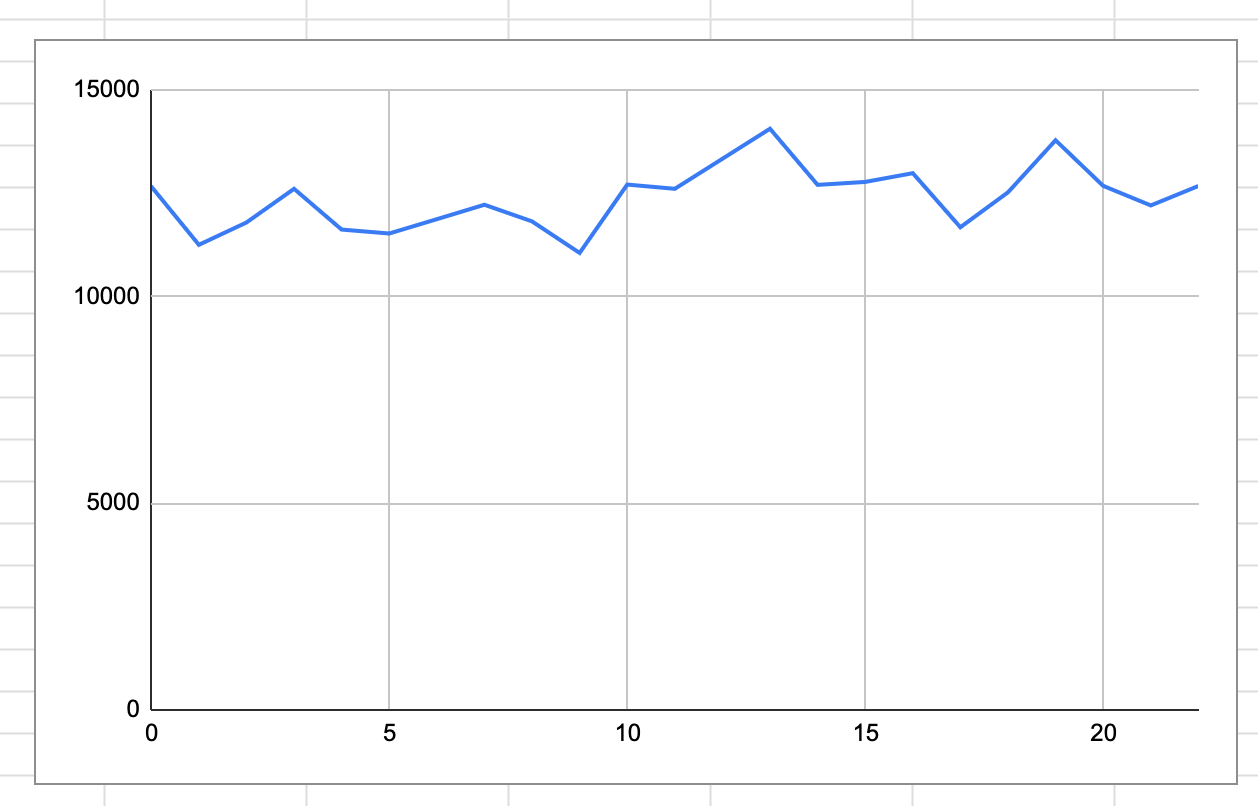

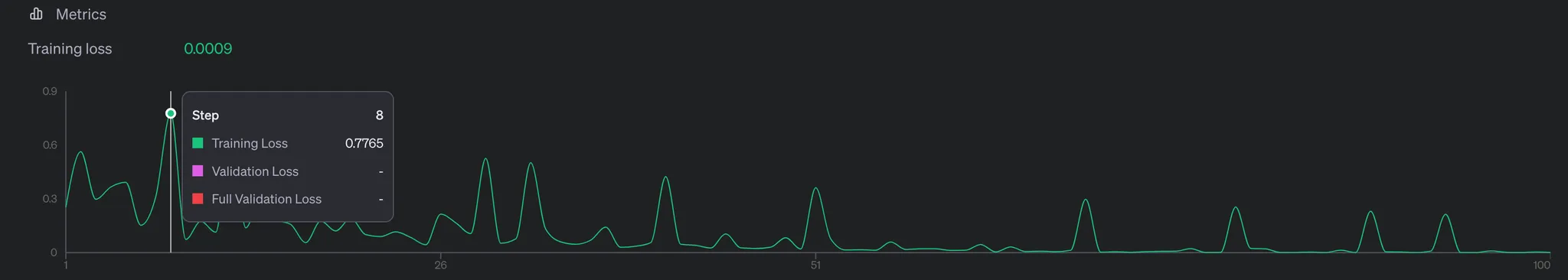

I tried this on a bunch of different code examples. Here’s a graph of one of the longer runs:

I was able to reproduce a lack of improvement on many different code examples & runs. 20 passes was around where I started running out of context window as the asm-differ output was pretty long.

So at this point I decided that the hypothesis was false for the out-of-box model. But we’re not done!

Fine tuning

I didn’t really go that deep in on fine-tuning. I was mostly curious about the flow for gpt-4o and if this would be a potential magic bullet.

I already had examples in a Q&A format. The OpenAI docs generally recommended to use 4o-mini if your task was already doable with 4o and you wanted to do it for cheaper after fine tuning. As I knew that the task wasn’t doable with 4o, I ended up opting for fine-tuning 4o.

The fine tuning UI was broken which was sad (I filed a ticket), but then I just curled their backend to start the fine-tuning job. $21 later, I realized that I didn’t have the money to keep doing this LOL. I did get a pretty graph:

The really low training loss was interesting to me. I spent some time testing the fine-tuned model. My observations:

- The fine-tuned model basically memorized the training examples. Given the exact same prompt, it would spit out C code that had a really low score of like 20, which is an over 99% match.

- However, varying the TEXT in the prompt (not the ASM) would make the match much worse, which sucked

- It didn’t generalize outside of the training set. Performance for ASM it hasn’t seen before remained at roughly the same thresholds with no improvement after additional passes.

I was hoping that fine-tuning the model would help it extrapolate to the “C that mwcc would compile to a given ASM.” It did not do that, and it also didn’t even figure out what type of C code would more easily compile with mwcc (e.g. it still required multiple passes to get compilable code) 😥.

Conclusion

I really enjoyed this project as my first serious AI project. If I didn’t try it, I would have gone insane: the first time over a year ago I saw ChatGPT spit out C code after looking at some assembly, I was haunted by what could be if AI was actually a magic decompiler. My inner demons were arguing about the ethics of solving this problem, but they got ahead of the actual reality:

AI isn’t a magic decompiler. But that doesn’t need to be the end of the story. On my GitHub for this project, I’ve detailed some alternate explorations that could be really fruitful, but I just ran out of time (or money). The problem statement is still compelling enough to me that I might work on it in the future.

Thanks for reading! Now I’ll probably go look for a job :)